The last few years have brought us significant progress in mobile cellular network performance. But many mobile applications cannot fully benefit from this advance due to inflated network latencies.

Latency has long been synomonous with mobile networking. Though progress has been made in recent years, the reductions to network latency have not kept pace with the increases in speed. As a consequence of this disparity, it is latency, not throughput, that is most often the factor limiting the performance of network transactions.

There are two logical sections to this chapter. The first portion will explore the particulars of mobile cellular networking that contribute to the latency problem. In the second portion software techniques to minimize the performance impact of elevated network latency will be introduced.

Latency represents the time needed for a data packet to transit across a network or series of networks. Mobile networks inflate the latencies already present in most Internet-based communications by a number of factors, including network type (e.g., HSPA+ vs. LTE), carrier (e.g., AT&T vs. Verizon) or circumstance (e.g., standing vs. driving, geography, time of day, etc.). It's difficult to state exact values for mobile network latency, but it can be found to vary from tens to hundreds of milliseconds.

Round-trip time (RTT) is a measure of the latency encountered by a data packet as it travels from its source to its destination and back. Round-trip time has an overwhelming effect upon the performance of many network protocols. The reason for this can be illustrated by the venerable sport of Ping-Pong.

In a regular game of Ping-Pong, the time needed for the ball to travel between players is hardly noticable. However as the players stand further apart they begin to spend more time waiting for the ball than doing anything else. The same 5-minute game of Ping-Pong at regulation distance would last for hours if the players stood a thousand feet apart, however as ridiculous as this seems. Substitute client and server for the 2 players, and round-trip time for distance between players, and you begin to see the problem.

Most network protocols play a game of Ping-Pong as part of their normal operation. These volleys, if you will, are the round-trip message exchanges needed to establish and maintain a logical network session (e.g., TCP) or carry out a service request (e.g., HTTP). During the course of these message exchanges little or no data is transmitted and network bandwidth goes largely unused. Latency compounds the extent of this underutilization to a large degree; every message exchange causes a delay of, at minimum, the network's round-trip time. The cumulative performance impact of this is remarkable.

Consider an HTTP request to download a 10KiB object would involve 4 message exchanges. Now figure a round-trip time of 100ms (pretty reasonable for a mobile network). Taking both of these figures into account and we arrive at an effective throughput of 10KiB per 400ms, or 25KiB per second.

Notice that bandwidth was completely irrelevant in the preceding example–no matter how fast the network the result remains the same, 25KiB/s. The performance of the previous operation, or any like it, can be improved only with a single, clear-cut strategy: avoid round-trip message exchanges between the network client and server.

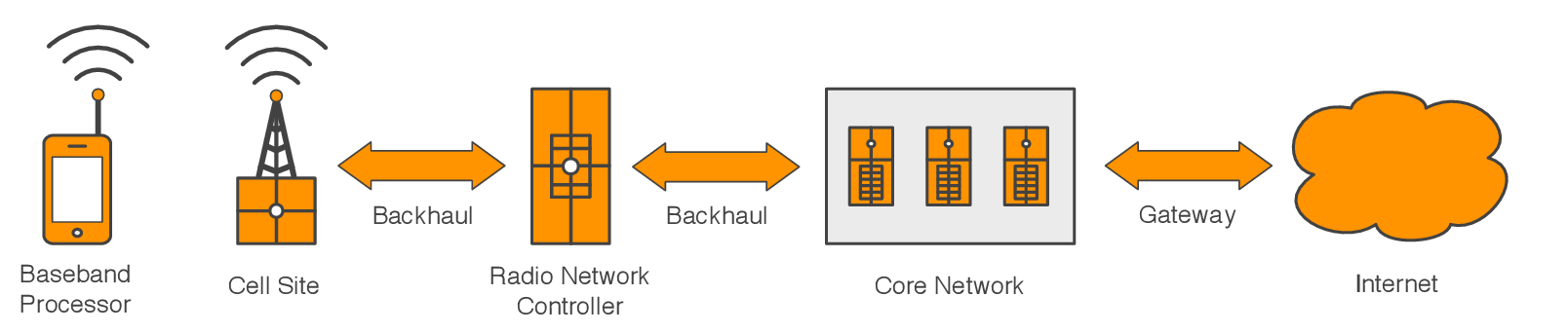

The following is a simplified introduction to the components and conventions of mobile cellular networks that factor into the latency puzzle.

A mobile cellular network is represented by a series of interconnected components having highly specialized functions. Each of these components is a contributor to network latency in some way, but to varying degrees. There exist conventions unique to cellular networks, such as radio resource management, that also factor into the mobile network latency equation.

Figure 10.1 - Components of a mobile cellular network

Inside most mobile devices are actually two very sophisticated computers. The application processor is responsible for hosting the operating system and applications, and is analogous to your computer or laptop. The baseband processor is responsible for all wireless network functions, and is analogous to a computer modem that uses radio waves instead of a phone line.1

The baseband processor is a consistent but usually neglible latency source. High-speed wireless networking is a frighteningly complicated affair. The sophisticated signal processing it requires contributes a fixed delay, in the range of microseconds to milliseconds, to most network communications.

A cell site, synonymous with transceiver base station or cell tower, serves as the access point for the mobile network. It's the cell site's responsibility to provide network coverage within a region known as a cell.

Like the mobile devices it serves, a cell site is burdened by the sophisticated processing associated with high-speed wireless networking, and contributes the same mostly neglible latency. However, a cell site must simultaneously service hundreds to thousands of mobile devices. Variances in system load will produce changes in throughput and latency. The sluggish, unreliable network performance at crowded public events is often the result of the cell site's processing limits being reached.

The latest generation of mobile networks have expanded the role of the cell site to include direct management of its mobile devices. Many functions that were formerly responsibilities of the radio network controller, such as network registration or transmission scheduling are now handled by the cell site. For reasons explained later in this chapter, this role shift accounts for much of the latency reduction achieved by the latest generation of mobile cellular networks.

A backhaul network is the dedicated WAN connection between a cell site, its controller, and the core network. Backhaul networks have long been, and continue to be notorious contributors of latency.

Backhaul network latency classically arises from the circuit-switched, or frame-based transport protocols employed on older mobile networks (e.g., GSM, EV-DO). Such protocols exhibit latencies due to their synchronous nature, where logical connections are represented by a channel that may only receive or transmit data during a brief, pre-assigned time period. In contrast, the latest generation of mobile networks employ IP-based packet-switched backhaul networks that support asynchronous data transmission. This switchover has drastically reduced backhaul latency.

The bandwidth limitations of the physical infrastructure are a continuing bottleneck. Many backhauls were not designed to handle the peak traffic loads that modern high-speed mobile networks are capable of, and often demonstrate large variances in latency and throughput as they become congested. Carriers are making efforts to upgrade these networks as quickly as possible, but this component remains a weak point in many network infrastructures.

Conventionally, the radio network controller manages the neighboring cell sites and the mobile devices they service.

The radio network controller directly coordinates the activities of mobile devices using a message-based management scheme known as signaling. As a consequence of topology all message traffic between the mobile devices and the controller must transit through a a high-latency backhaul network. This alone is not ideal, but is made worse by the fact many network operations, such as network registration and transmission scheduling, require multiple back-and-forth message exchanges. Classically, the radio network controller has been a primary contributor of latency for this reason.

As mentioned earlier, the controller is absolved of its device management duties in the latest generation of mobile networks, with much of these tasks now being handled directly by the cell sites themselves. This design decision has eliminated the factor of backhaul latency from many network functions.

The core network serves as the gateway between the carrier's private network and the public Internet. It's here where carriers employ in-line networking equipment to enforce quality-of-service policies or bandwidth metering. As a rule any interception of network traffic will introduce latency. In practice this delay is generally neglible but its presence should be noted.

One of the most significant sources of mobile network latency is directly related to the limited capacity of mobile phone batteries.

The network radio of a high-speed mobile device can consume over 3 Watts of power when in operation. This figure is large enough to drain the battery of an iPhone 5 in just over one hour. For this reason mobile devices remove or reduce power to the radio circuitry at every opportunity. This is ideal for extending battery life but also introduces a startup delay any time the radio circuitry is repowered to deliver or receive data.

All mobile cellular network standards formalize a radio resource management (RRM) scheme to conserver power. Most RRM conventions define three states–active, idle and disconnected–that each represent some compromise between startup latency and power consumption.

Figure 10.2 - Radio resource management state transitions

Active represents a state where data may be transmitted and received at high speed with minimal latency.

This state consumes large amounts of power even when idle. Small periods of network inactivity, often less than second, trigger transition to the lower power idle state. The performance implication of this is important to note: sufficiently long pauses during a network transaction can trigger additional delays as the device fluctuates between the active and idle states.

Idle is a compromise of lower power usage and moderate startup latency.

The device remains connected to the network, unable to transmit or receive data but capable of receiving network requests that require the active state to fulfill (e.g., incoming data). After a reasonable period of network inactivity, usually a minute or less, the device will transition to the disconnected state.

Idle contributes latency in two ways. First, it requires some time for the radio to repower and synchronize its analog circuitry. Second, in an attempt to conserve even more energy the radio listens only intermittenly and slightly delays any response to network notifications.

Disconnected has the lowest power usage with the largest startup delays.

The device is disconnected from the mobile network and the radio deactivated. The radio is activated, however infrequently, to listen for network requests arriving over a special broadbcast channel.

Disconnected shares the same latency sources as idle plus the additional delays of network reconnection. Connecting to a mobile network is a complicated process involving multiple rounds of message exchanges (/i.e., signaling). At minimum, restoring a connection will take hundreds of milliseconds, and it's not unusual to see connection times in the seconds.

Now onto the things we actually have some control over.

The performance of network transactions are disproportionately affected by inflated round-trip times. This is due to the round-trip message exchanges intrinsic to the operation of most network protocols. The remainder of this chapter focuses on understanding why these messages exchanges are occurring and how their frequency can be reduced or even eliminated.

Figure 10.3 - Network protocols

The Transport Control Protocol (TCP) is a session-oriented network transport built atop the conventions of IP networking. TCP affects the error-free duplex communications channel essential to other protocols such as HTTP or TLS.

TCP demonstrates a lot of the round-trip messaging we are trying to avoid. Some can be eliminated with adoption of protocol extensions like Fast Open. Others can be minimized by tuning system parameters, such as the initial congestion window. In this section we'll explore both of these approaches while also providing some background on TCP internals.

Initiating a TCP connection involves a 3-part message exchange convention known as the three-way handshake. TCP Fast Open (TFO) is an extension to TCP that eliminates the round-trip delay normally caused by the handshake process.

The TCP three-way handshake negotiates the operating parameters between client and server that make robust 2-way communication possible. The initial SYN (synchronize) message represents the client's connection request. Provided the server accepts the connection attempt it will reply with a SYN-ACK (synchronize and acknowledge) message. Finally, the client acknowledges the server with an ACK message. At this point a logical connection has been formed and the client may begin sending data. If you're keeping score you'll note that, at minimum, the three-way handshake introduces a delay equivalent to the current round-trip time.

Figure 10.4 - TCP 3-Way handshake

Conventionally, outside of connection recycling, there’s been no way to avoid the delay of the TCP three-way handshake. However, this has changed recently with introduction of the TCP Fast Open IETF specification.

TCP Fast Open (TFO) allows the client to start sending data before the connection is logically established. This effectively negates any round-trip delay from the three-way handshake. The cumulative effect of this optimization is impressive. According to Google research TFO can reduce page load times by as much as 40%. Although still only a draft specification, TFO is already supported by major browsers (Chrome 22+) and platforms (Linux 3.6+), with other vendors pledging to fully support it soon.

TCP Fast Open is a modification to the three-way handshake allowing a small data payload (e.g., HTTP request) to be placed within the SYN message. This payload is passed to the application server while the connection handshake is completed as it would otherwise.

Earlier extension proposals like TFO ultimately failed due to security concerns. TFO addresses this issue with the notion of a secure token, or cookie, assigned to the client during the course of a conventional TCP connection handshake, and expected to be included in the SYN message of a TFO-optimized request.

There are some minor caveats to the use of TFO. The most notable is lack of any idempotency guarantees for the request data supplied with the initiating SYN message. TCP ensures duplicate packets (duplication happens frequently) are ignored by the receiver, but this same assurance does not apply to the connection handhshake. There are on-going efforts to standardize a solution in the draft specification, but in the meantime TFO can still be safely deployed for idempotent transactions.

The initial congestion window (initcwnd) is a configurable TCP setting with large potential to accelerate smaller network transactions.

A recent IETF specification promotes increasing the common initial congestion window setting of 3 segments (i.e., packets) to 10. This proposal is based upon extensive research conducted by Google that demonstrates a 10% average performance boost. The purpose and potential impact of this setting can't be appreciated without an introduction TCP's congestion window (cwnd).

TCP guarantees reliability to client and server when operating over an otherwise unreliable network. This amounts to a promise that all data are received as they were sent, or at least appear to be. Packet loss is the largest obstacle to meeting the contract of reliablity; it requires detection, correction and prevention.

TCP employs a positive acknowledgement convention to detect missing packets in which every sent packet should be acknowledged by its intended receiver, the absence of which implies it was lost in transit. While awaiting acknowledgement, transmitted packets are preserved in a special buffer referred to as the congestion window. When this buffer becomes full, an event known as cwnd exhaustion, all transmission stops until receiver acknowledgements make room available to send more packets. These events play a significant role in TCP performance.

Apart from the limits of network bandwidth, TCP throughput is ultimately constrained by the frequency of cwnd exhaustion events, the likelihood of which relates to the size of the congestion window. Achieving peak TCP performance requires a congestion window complementing current network conditions: too large and it risks network congestion–an overcrowding condition marked by extensive packet loss; too small and precious bandwidth goes unused. Logically, the more known about network conditions the more likely an optimal congestion window will be chosen. Reality is that key network attributes, such as capacity and latency, are difficult to measure and constantly in flux. It complicates matters further that any Internet-based TCP connection will span across numerous networks.

Lacking means to accurately determine network capacity, TCP instead infers it from the conditon of network congestion. TCP will expand the congestion window just to the point it begins seeing packet loss, suggesting somewhere downstream there's a network unable to handle the current transmission rate. Employing this congestion avoidance scheme, TCP eventually minimizes cwnd exhaustion events to the extent it consumes all the connection capacity it has been allotted. And now, finally, we arrive at the purpose and importance of the TCP initial congestion window setting.

Network congestion can't be detected without signs of packet loss. A fresh, or idle connection lacks evidence of the packet losses needed to establish an optimal congestion window size. TCP adopts the tact it's better to start with a congestion window with the least likelihood of causing congestion; this originally implied a setting of 1 segment (~1480 bytes), and for some time this was recommended. Later experimentation demonstrated a setting as high as 4 could be effective. In practice you usually find the initial congestion window set to 3 segments (~4 KiB).

The initial congestion window is detrimental to the speed of small network transactions. The effect is easy to illustrate. At the standard setting of 3 segments, cwnd exhaustion would occur after only 3 packets, or 4 KiB, were sent. Assuming the packets were sent contiguously, the corresponding acknowledgements will not arrive any sooner than the connection's round-trip time allows. If the RTT were 100 ms, for instance, the effective transmission rate would be a pitiful 400 bytes/second. Although TCP will eventually expands its congestion window to fully consume available capacity, it gets off to a very slow start. As a matter of fact, this convention is known as slow start.

To the extent slow start impacts the performance of smaller downloads it begs reevaluating the risk-reward proposition of the initial congestion window. Google did just that and discovered an initial congestion window of 10 segments (~14 KiB) generated the most throughput for the least congestion. Real world results demonstrate a 10% overall reduction in page load times. Connections with elevated round-trip latencies will experience even greater results.

Modifying the intial congestion window from its default is not straightforward. Under most server operating systems it's as a system-wide setting configurable only by a priviledged user. Rarely can this setting be configured on the client by a non-priviledged application, or even at all. It's important to note a larger initial congestion window on the server accelerates downloads, whereas on the client it accelerates uploads. The inability to change this setting on the client implies special efforts should be given to minimizing request payload sizes.

This section dicusses techniques to mitigate the effects high round-trip latencies have upon Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) performance.

Keepalive is an HTTP convention enabling use of the same TCP connection across sequential requests. At minimum a single round-trip–required for TCP's three-way handshake–is avoided, saving tens or hundreds of milliseconds per request. Further, keepalive has the additional, and often unheralded, performance advantage of preserving the current TCP congestion window between requests, resulting in far fewer cwnd exhaustion events.

Figure 10.5 - HTTP pipelining

Effectively, pipelining distributes the delay of a network round-trip amongst multiple HTTP transactions. For instance, 5 pipelined HTTP requests across a 100ms RTT connection will incur an average round-trip latency of 20ms. For the same conditions, 10 pipelined HTTP requests reduce the average latency to 10ms.

There are notable downsides to HTTP pipelining preventing its wider adoption, namely a history of spotty HTTP proxy support and suceptibility to denial-of-service attacks.

Transport Layer Security (TLS) is a session-oriented network protocol allowing sensitive information to be securely exchanged over a public network. While TLS is highly effective at securing communications its performance suffers when operating on high latency networks.

TLS employs a complicated handshake involving two exchanges of client-server messages. A TLS-secured HTTP transaction may appear noticably slower for this reason. Often, observations that TLS is slow are in reality a complaint about the multiple round-trip delays introduced by its handshake protocol.

Figure 10.6 - DNS query

Generally, the hosting platform provides a cache implementation to avoid frequent DNS queries. The semantics of DNS caching are simple. Each DNS response contains a time-to-live (TTL) attribute declaring how long the result may cached. TTLs can range from seconds to days but are typically on the order of several minutes. Very low TTL values, usually under a minute, are used to affect load-distribution or minimize downtime from server replacement or ISP failover.

The native DNS cache implementations of most platforms don't account for elevated round-trip times of mobile networks. Many mobile applications could benefit from a cache implementation that augments or replaces the stock solution. Suggested here are several cache strategies, that if deployed for application use, will eliminate any random and spurious delays caused by unnecessary DNS queries.

Highly-available systems usually rely upon redundant infrastructures hosted within their IP address space. Low-TTL DNS entries have the benefit of reducing the time a network client may refer to the address of a failed host, but at the same time triggers a lot of extra DNS queries. The TTL is a compromise between minimizing downtime and maximizing client performance.

It makes no sense to generally degrade client performance when server failures are the exception to the rule. There is a simple solution to this dilemma, rather than strictly obeying the TTL a cached DNS entry is only refreshed when a non-recoverable error is detected by higher-level protocol such as TCP or HTTP. Under most scenarios this technique emulates the behavior of a TTL-conformant DNS cache while nearly eliminating the performance penalties normally associated with any DNS-based high-availability solution.

It should be noted this cache technique would likely be incompatible with any DNS-based load distribution scheme.

Asynchronous refresh is an approach to DNS caching that (mostly) obeys posted TTLs while largely eliminating the latency of frequent DNS queries. An asynchronous DNS client library, such as c-ares, is needed to implement this technique.

The idea is straightforward, a request for an expired DNS cache entry returns the stale result while a non-blocking DNS query is scheduled in the background to refresh the cache. If implemented with a fallback to blocking (i.e., synchronous) queries for very stale entries, this technique is nearly immune to DNS delays while also remaining compatible with many DNS-based failover and load-distribution schemes.

Mitigating the impact of mobile networks' inflated latency requires reducing the network round-trips that exacerbate its effect. Employing software optimizations solely focused on minimizing or eliminating round-trip protocol messaging is critical to surmounting this daunting performance issue.

In fact many mobile phones manage the baseband processor with an AT-like command set.↩